Thanks again for taking the time to read The Flag Poll. Responses to the first post blew me away. That post is here if you missed it.

Today’s post is the first of three on what I perceive to be the received wisdom of flag design. The best practices, if you will. The point of this exercise is threefold. First, I want to situate you, loyal reader, in the mainstream of flag design. Second, I want to lay out the vocabulary and concepts we can use to critique the flags we see. Hopefully, this vocabulary will serve you well as you think about the flags around you. Finally, I want to start laying the groundwork for future posts about my own views on flag design, which will differ in some ways from this mainstream line of thinking.

If you Google “flag design principals,” you will see a suggested correction to your spelling to “principles,” and you will feel much like your humble blogger did in writing this paragraph: embarrassed. If you then search “flag design principles” or “what makes a good flag,” all of your top hits will either cite to—or not cite to but should cite to—the famous pamphlet Good Flag, Bad Flag (GFBF). GFBF is the flag design Bible. Roman Mars’s flag design TED Talk referenced GFBF extensively, while YouTuber CGP Grey implicitly relied on GFBF in setting criteria for judging U.S. state flags.

Ted Kaye, personal hero and longtime member of the North American Vexillological Association, compiled GFBF based on feedback from the flag design community. GFBF gives five basic principles for flag designers to follow. The five principles are as follows:

Keep it simple

Use meaningful symbolism

Use 2-3 basic colors

No lettering or seals

Be distinctive or be related

Before we break these down, let’s pause to clarify what GFBF is not. It is not, or at least should not be, a straitjacket on flag design. As the pamphlet notes, the principles are really “guidelines, not rules” for flag designers. Kaye’s point in GFBF is that designers should “depart from these five principles only with caution and purpose.” That’s an important caveat, and one that I think is often lost. There will be a future post on this, but if you go to r/vexillology or look at many of the proposed (and adopted) new flags for states and municipalities…they kind of all look the same. People see “principles” and they take that to mean “rules,” and all of a sudden you have fifteen flags that look like they came from the same designer.

Unsurprisingly, the Germans have a word for what the GFBF principles really are. The German translation of GFBF (Gute Flagge, Schlechte Flagge) calls the five principles Faustregeln, which translates to “rules of thumb,” not “principles.” German has a separate word—Grundregeln—which is not used here and translates more directly as principles.

In any case, I will go through each one of these five principles. After explaining each principle, I’ll show how it has real merit, but also real potential to stifle great flags if taken too literally. We will start today with the very first principle (well, Faustregel). I will go through two more in my next post, and two more the week after.

Keep it Simple

From GFBF: “The flag should be so simple that a child can draw it from memory.”

Flags are very different from, say, signatures or seals. Signatures and seals are viewed up close. You see a signature at the bottom of a check or a note your mom totally wrote your second grade teacher to get you out of class. You see seals on diplomas and jury summons. For both signatures and seals, the reader has the time to closely examine the design and any intricate details. Plus, the seal or signature is right in front of the reader’s eyes. A flag on the other hand has to be seen from a very long distance. It has to be seen as often in a breeze as when there is no wind at all. Plus, someone looking at a flag doesn’t have all day to make out its design. For these reasons, a flag with intricate designs or copious elements is just a waste of cloth. No one will be able to make out these elements at a distance, particularly if there is wind or if they just take a quick glance. Here are a few flags that fail this rule of thumb. This intricacy tends to be much more of a problem at the state/local level than the international level.

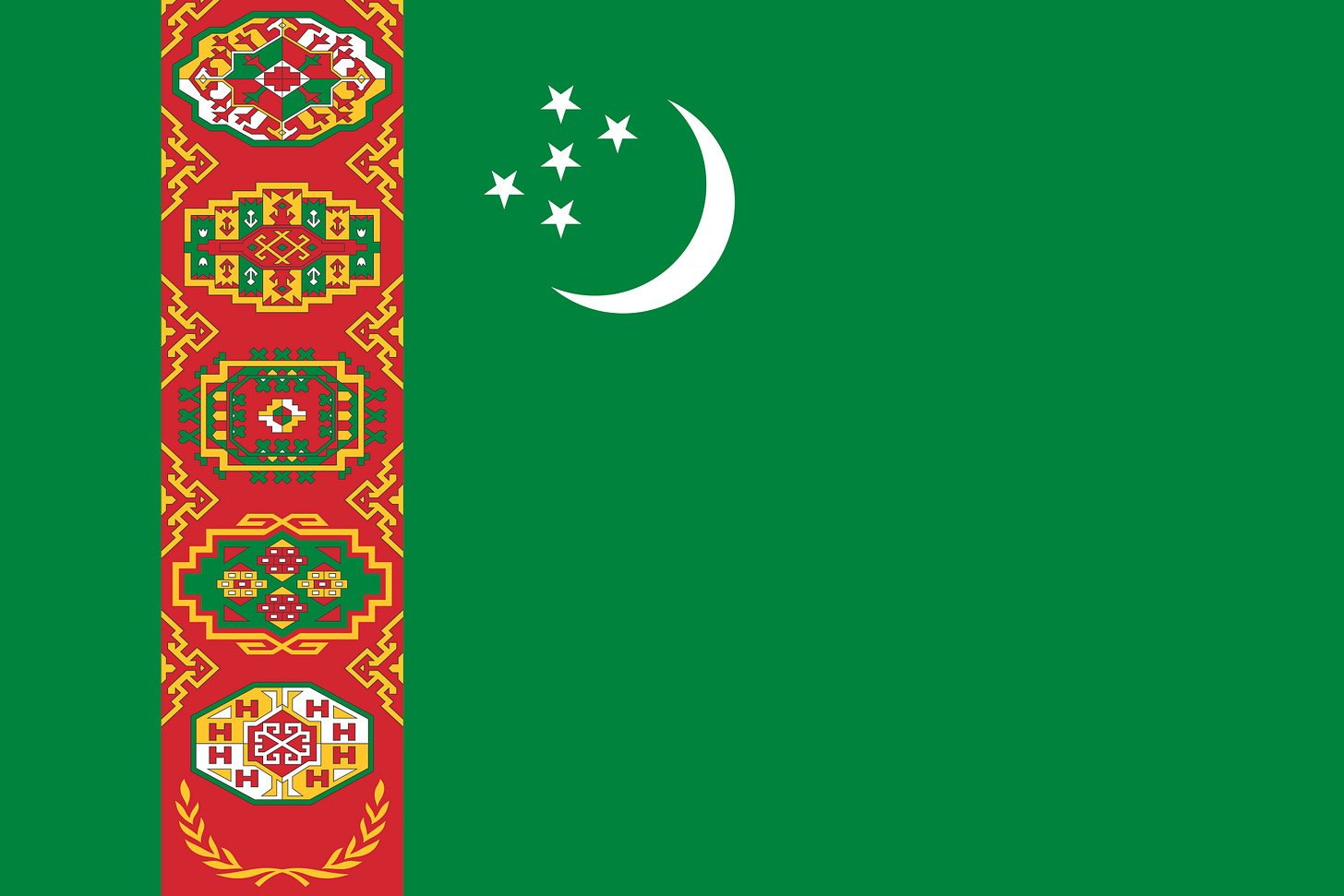

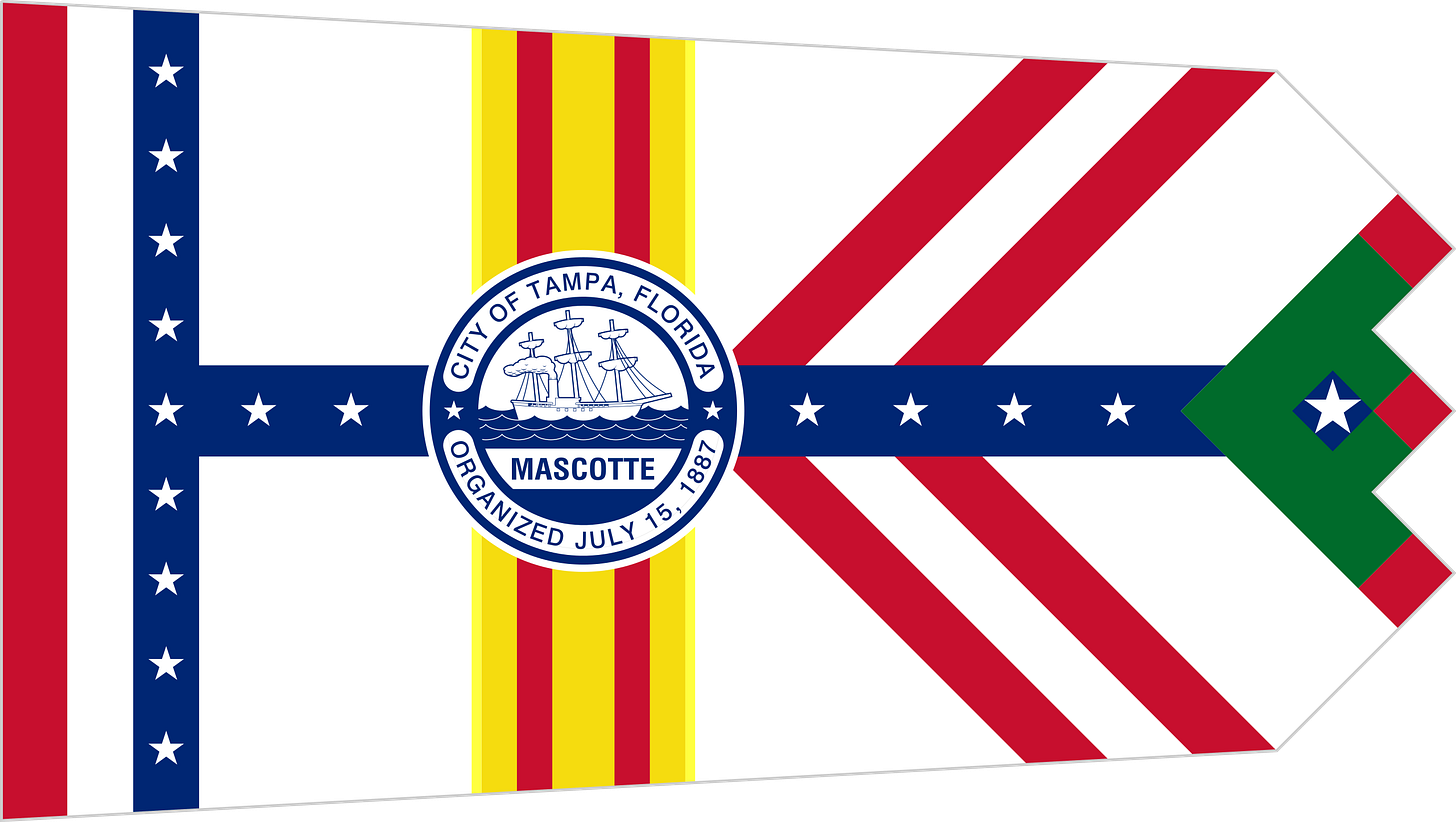

All of these flags are just, well, not simple. From fifty feet away, a flag consumer just will not be able to make out the ornate patterns on the Turkmen flag. The symbolism is cool (it is a set of five traditional rug patterns), but it is just not decipherable. And if there’s no wind, it will likely just look like a green flag at a distance, as this picture from the UN headquarters in New York shows. Minnesota’s old flag is not much better. Seals have a separate principle decrying them (more on that in a few weeks), but Minnesota’s old flag took things to a whole new level by adding stars, rings, and circles to the seal. Tampa’s flag is a non-quadrilateral mess that looks like a kite Evil Knievel would own, while Milwaukee’s flag has been publicly humiliated in other channels.

Here are a few flags that fit the simplicity principle and are just awesome.

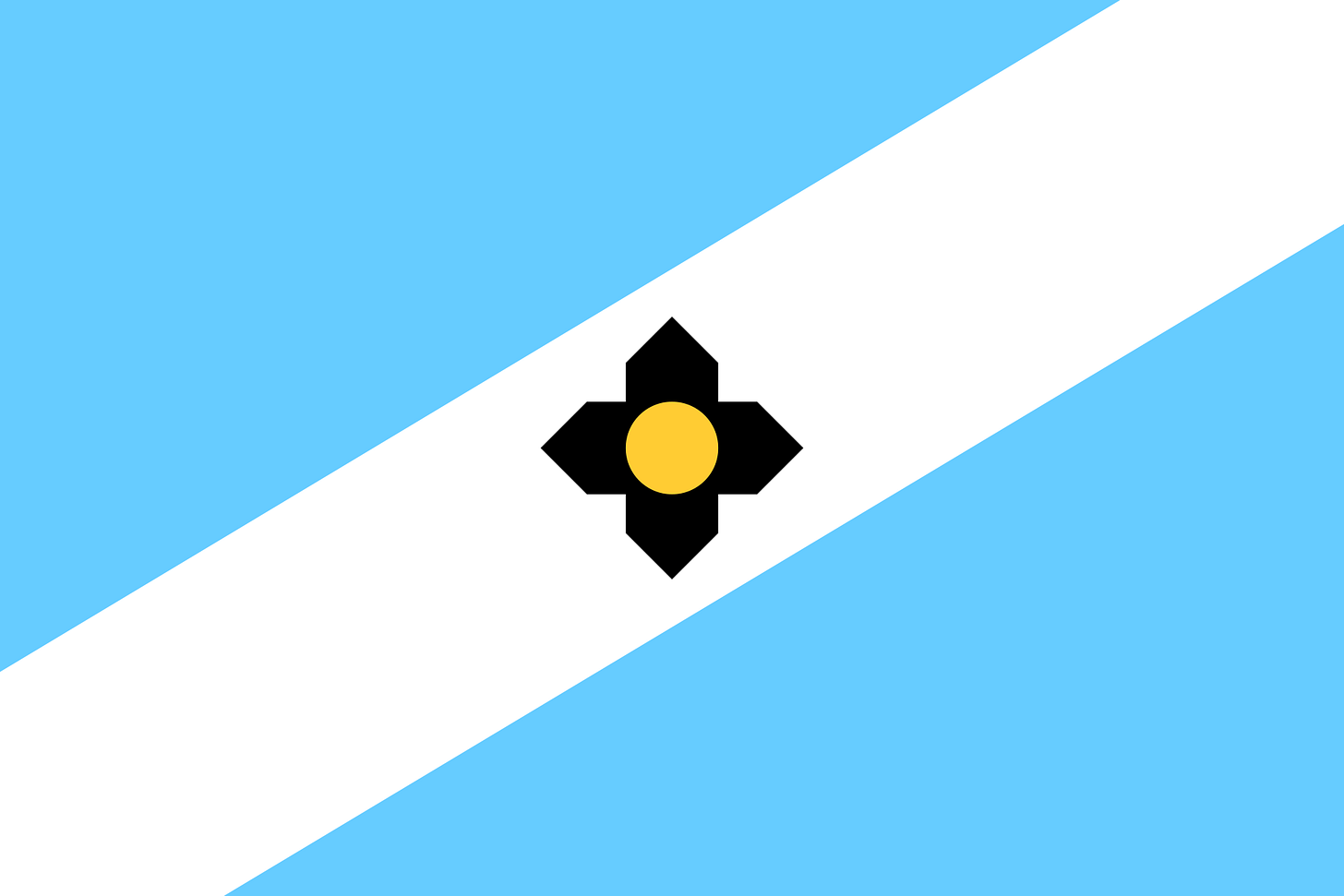

All of these flags have great symbolism too, but focus for now on how simple their designs are. Minnesota took the words from their original flag “Étoile du Nord” and actually added it onto their flag as a design element with that eight-sided North Star. Trinidad and Tobago’s flag is a masterpiece (the Caribbean nations are flag design heaven), and you can see its use everywhere. For example, rapper Trinidad James features the flag quite prominently in his music videos, including as an accessory.

All three flags are pretty easily identifiable at a distance. And that is saying something for Minnesota, as the majority of state flags are some shade of blue. But the two-tone flag just pops. The Trinidad and Tobago and Madison flags’ bright colors and sashes (the vexillological terms for sashes are “bend” and “bend sinister” depending on the direction) also are impossible to miss.

The litmus test of a child being able to draw from memory is a pretty good one. I am confident that a child in Trinidad (or Tobago) or in Madison could draw their flags from memory. But not even a child prodigy in vexillology would be able to draw Tampa’s. I would still urge readers not to follow the test too closely, as it is certainly not infallible. Take for example the flag of Maryland. Maryland’s flag—based on the arms of Lord Baltimore—is complete chaos. I could not draw this from memory…I’m not even sure I could copy this over. But Maryland’s flag is, well, incredible. If you ever went to college with someone from Maryland, odds are they had this flag on their wall.

I think a literal application of the litmus test is also unwise. Some flags are complicated, but are still great. For example, both Bhutan and Wales have dragons on their flags, while Argentina and Uruguay have the Sol de Mayo, an Incan sun symbol. A child could not draw any of these flags from memory, but could certainly get the colors and elements generally right.

Bhutan and Maryland are examples of flags that are not simple, but are very good flags. There are plenty of other flags like this, as I show in the brief gallery below. Many of these flags would fail the child-drawing litmus test and are certainly more complicated than GFBF calls for.

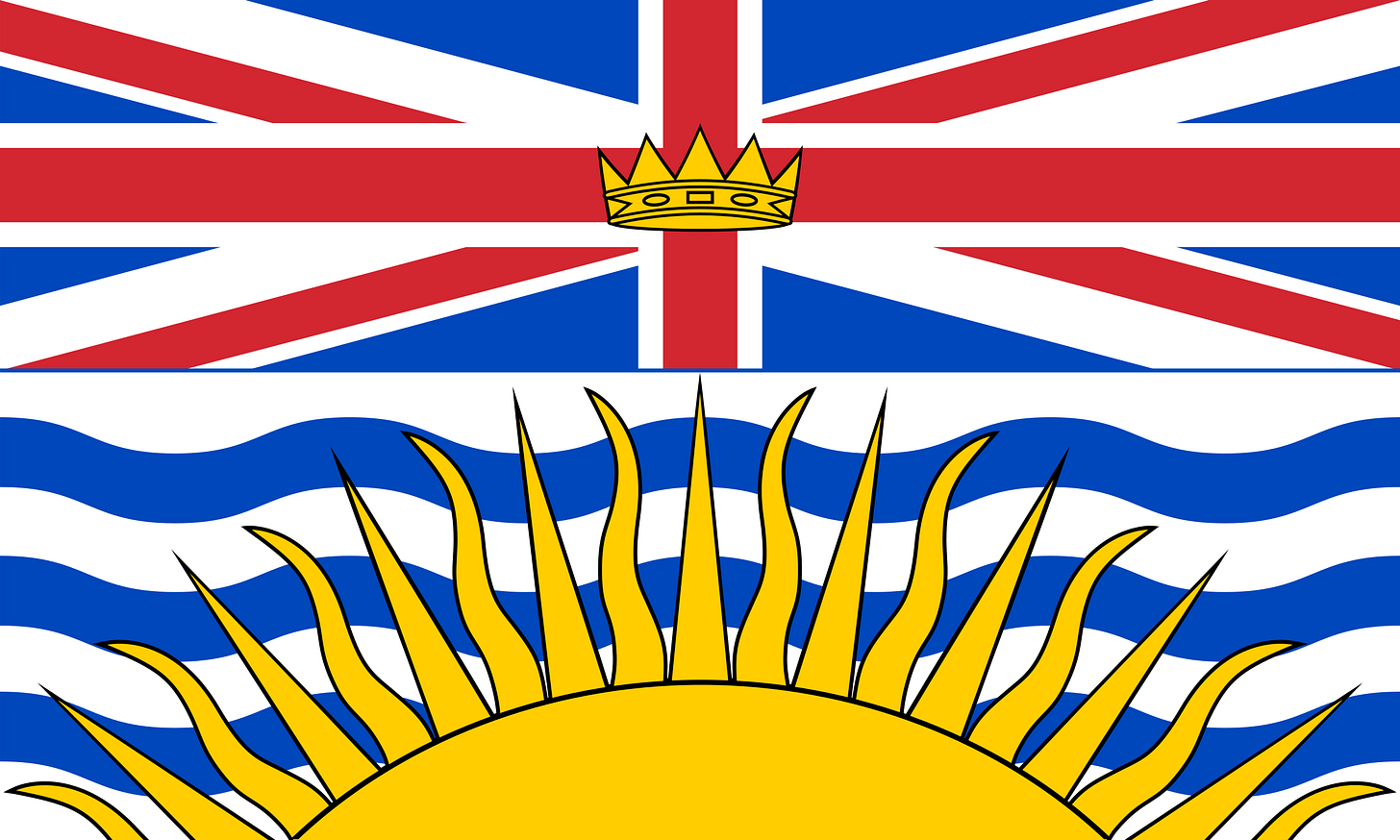

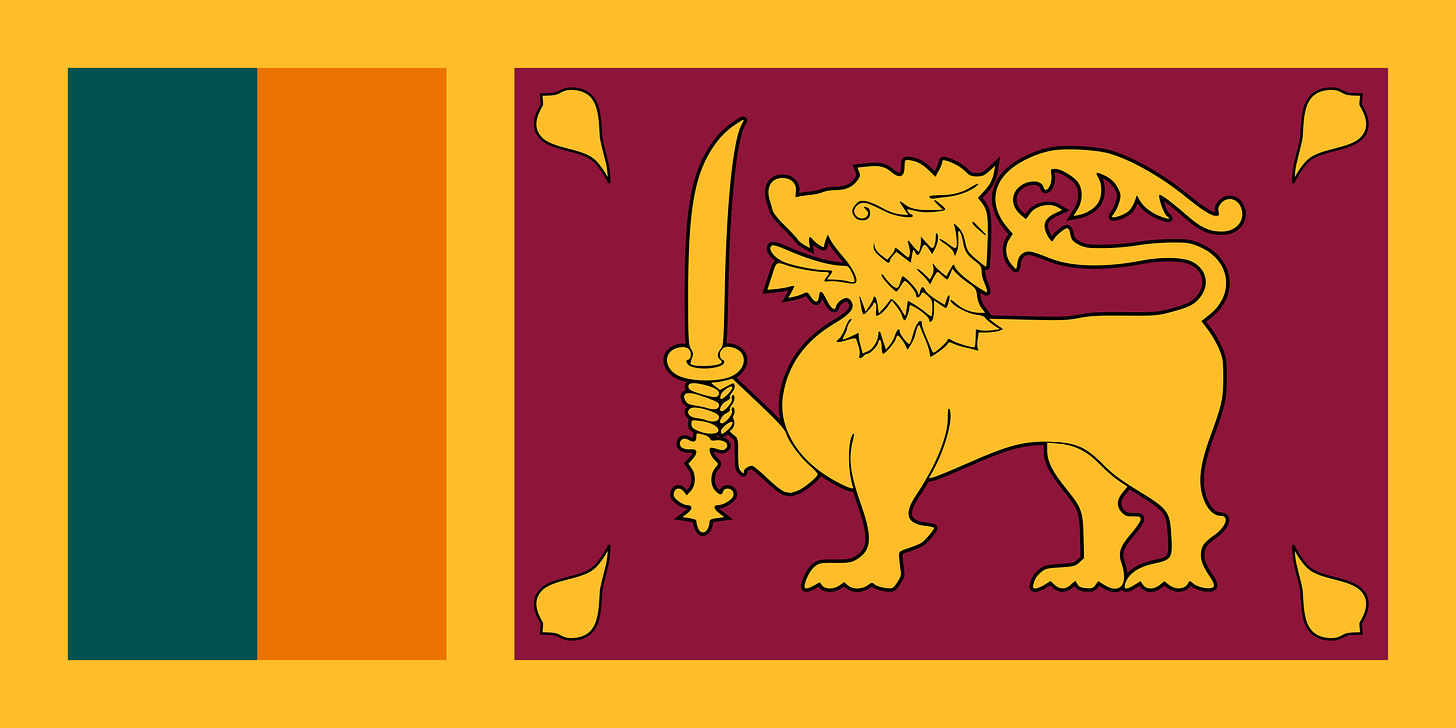

I do not love these flags, but they are certainly good flags that are not simple. How to reconcile these relatively complicated flags with our GFBF principle that is directionally accurate? Well for one, we can call the principle a rule of thumb. But really, I think it is that minute detail is almost always a no-go. If you are going to go ornate like the dragon on the Bhutanese flag or the lion on the Sri Lankan flag, then go big. Make it so that even from a distance, your audience can tell what the flag’s elements are. For example, British Columbia’s sun and waves can actually be seen from a distance, as I virtually saw myself through Google Street View. It’s when designers go with small, minute details that we really run into problems, like Milwaukee’s flag. That flags itself includes two mini flags…

Next week, we move to principles 2 and 3: using meaningful symbolism and using 2-3 basic colors, a principle that is let down by many of the flags in this post. As always, feel free to raise any flag queries at flagpoll@substack.com.

As a first time reader and new subscriber, what are your thoughts on the flag of the International Federation of Vexillological Associations? https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c4/Flag_of_FIAV.svg/1280px-Flag_of_FIAV.svg.png