Welcome to The Flag Poll—your new home for hot takes, hard-hitting analysis, and commentary about the world of flags and flag design. In my writing, I want to show you (soon-to-be) loyal readers why I love flags and why you should too, or why you should at least pay attention to them.

My goal for the first few posts after this one is to run through the mainstream views on what makes for a “good” flag. In doing so, I want to start to define my own standards for judging flags. As you will see, my view is that it is much easier to define tests for bad flags than it is to define tests for good flags. Flag design has had its moment, driven by Roman Mars’s famous Ted Talk (a great overview of the subject), and CGP Grey’s YouTube video. Just in the last ten years, Utah, Mississippi, and dozens of municipalities have reacted by redesigning their flags. I think as a result of this trend, flag design has reached a worrying rut of groupthink, and I hope this blog can counteract that.

Before I move onto my overview and critique of the received wisdom of flag design, I want to ask a more fundamental question. Why? Why should we care about flags?

To this, I have two answers. First, flags are just another form of design, and good design rules. We spend a lot of time as a society on other kinds of design. We watch Architectural Digest videos (even Josh Weissman—famous for making cooking videos on YouTube—has one), fashion shows, and product releases. Some corporate logos are etched into our brains; an entire phase of my high school experience was dedicated to playing “the logo game” in study hall. We appreciate good design, like the iPod, the tissue box, or the Nike swoosh. We disdain bad design, like the Microsoft Zune, airline seats, or HBO’s rebranding as Max. Flags should receive this level of scrutiny.

People also care about good flags. Ask yourself what your state and city flags look like. Right now. Take the time, and then look them up. If you don’t know what they look like, it’s probably because you suffer from a bad flag! As Roman Mars has explained, good flags are flown by citizens and businesses alike, buttressing civic pride. Good flags give design elements for the entire populace to draw from, like Chicago’s women’s soccer team, which gets its name, badge, and jerseys from the city’s gorgeous flag. Simply put, it is hard to miss a good flag.

My second answer is a bit deeper. I love flags because they almost always reveal nuance about what the people that designed and approved the flag hold—or held—dear. Flags ultimately represent cities, states, and countries, and the people that design flags want flags that somehow reflect these polities. A flag is basically a brief introduction to a community. Flags may highlight people, or history, or geography, and each element gives a little clue into what that community cherishes or values.

Take for example the flag of the U.K., arguably the most iconic national flag there is. The three crosses that make up the Union Jack represent England (red cross), Scotland (blue background and white diagonal cross), and Northern Ireland (red diagonal cross). Its first design with just two crosses emerged in 1606, a few years after James III united the English and Scottish crowns. George III proclaimed a redesign by royal decree in 1801 to add the cross of Saint Patrick when Great Britain united with Ireland. Attentive readers will wonder where Wales is. Wales had legally merged into England before the era of national flags had really kicked off. See? Flags tell us a lot. In that little introduction to the Union Jack, one learns about the different component parts of the U.K., the U.K.’s own value of these subunits being united and (somewhat) coequal, and how two of these subunits have a longer history together than the others.

What about the U.S. flag? Everybody knows that our flag has fifty stars for each state, and thirteen stripes for each of the original thirteen states. But until 1818, a star and a stripe was added for each new state. In fact, the Star Spangled Banner was not only written about an American flag, it was written about one that had fifteen stars and fifteen stripes, thanks to the additions of Kentucky and Vermont. That 1818 reversion to a star for each state but only thirteen stripes says a lot about our nation’s own view of its history and our form of government.

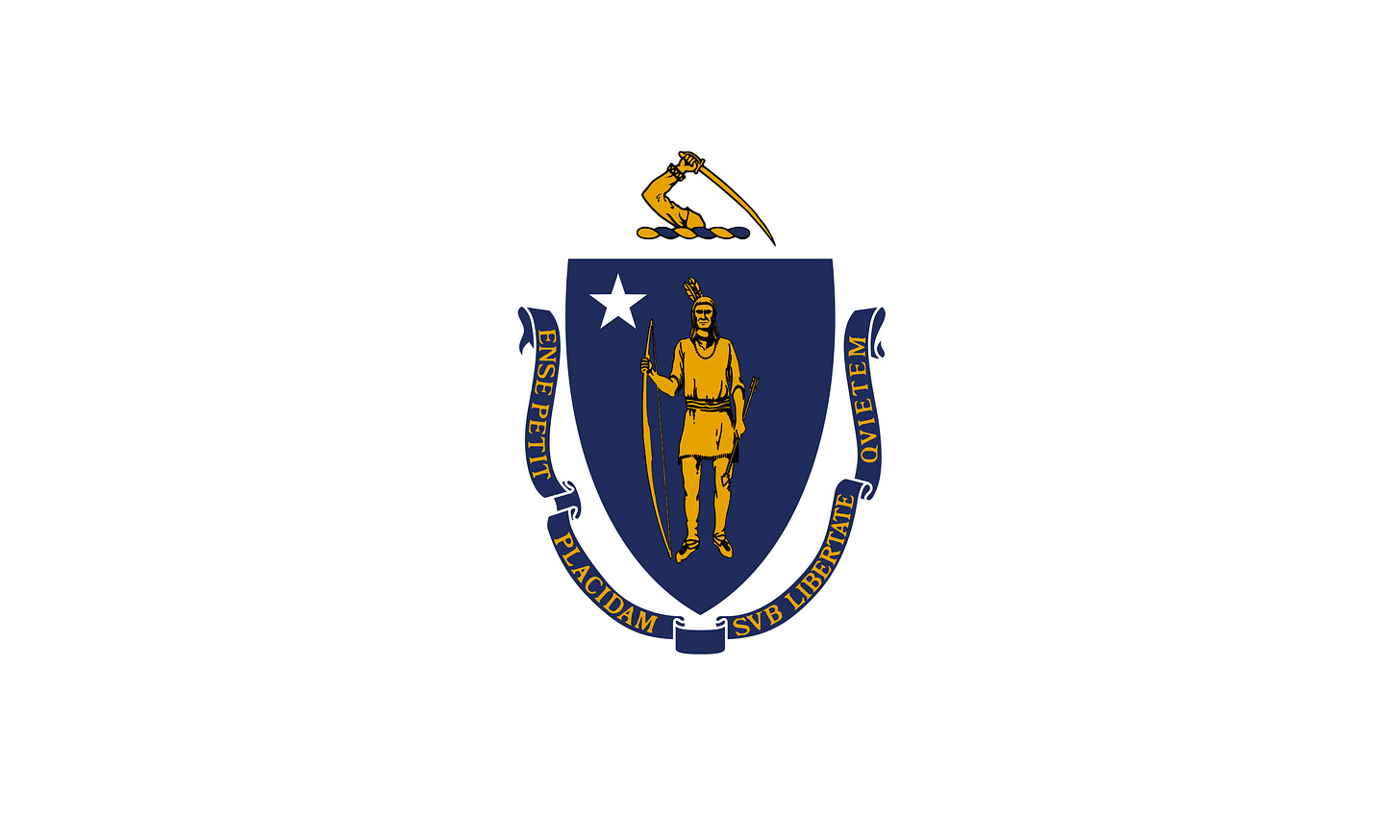

One last—and perhaps less rosy—example is my home state of Massachusetts. Our flag is frankly quite boring, and has not fared well in scholarly or lay rankings. A pity given the wealth of flags in the Commonwealth’s arsenal (more on that in a few weeks, or maybe months). But it has several elements that reveal insights into Massachusetts history.

Start with the Latin text, which loosely translates to “By the sword we seek peace, but peace only under liberty.” The quote itself was not spoken in Massachusetts or by one of its citizens, but certainly concords with the Commonwealth’s rebellious history. There’s a star, representing Massachusetts’s position as a state. Ho-hum.

But I want to focus on the other two elements: the Native American in the middle of the shield and the hand above the shield. The Native American in the middle of the shield notably has his arrows pointing downwards, in a gesture of peace, or as the Commonwealth’s history suggests, possibly surrender. You then have an arm holding a sword—supposedly modeled off of one that was owned by Plymouth Colony military officer Myles Standish. There are many interpretations of this sword, and it is hard to conclude which is correct. It could show that liberty is worth sacrificing an arm for, or to show that it took fighting to win the Commonwealth’s liberty, while some say it is blatant white supremacy.

Regardless of who is right, these two images taken together give a pretty blunt portrayal of the Commonwealth. It shows the values and history of the Commonwealth—freedom and liberty, but also tension with its Indigenous communities. Just about every flag tells similar stories.

In a state-government skeptic’s paradigmatic case of government in inaction, a state commission tasked with studying a redesign concluded that one was merited and promptly disbanded without coming up with specific proposals or next steps.

Next time, we will continue our vexillological voyage by taking a look at the modern gold standard of guidance regarding flag design—those of the North American Vexillological Association. I’ll explain where I see flaws in their approach, as well as successes. As always, feel free to drop a line at flagpoll@substack.com, or in the comments.

Zune reference. You've earned my sub

Chicago is #1